On The Shelf

“Great art is always emotionally intelligent, rarely rationally so.”

Michael Craig-Martin

Every so often, I find myself deep in thought about the evolution of ideas — how they originate and evolve out of nothing. For me, this process feels mystic, a dance between the known and unknown. In fact, I continue to drag my conversations with friends, much to their polite impatience, into these spirals of fascination.

After all, it is almost impossible to not be fascinated by this elusive process. One moment, there is nothing, and then, inexplicably, there’s something there – an idea, fully realized, demanding attention and energy with a sense of gravity around it that feels inevitable. Despite my best efforts, the idea’s origin always seems impossible to pinpoint, like trying to draw water from an invisible well.

These thoughts followed me like shadows when I first encountered Michael Craig-Martin’s On the Shelf. Standing there, before the piece, I felt a sense of understanding that had evaded words. It took three visits, each a quiet pilgrimage, before I could even begin to put it into language.

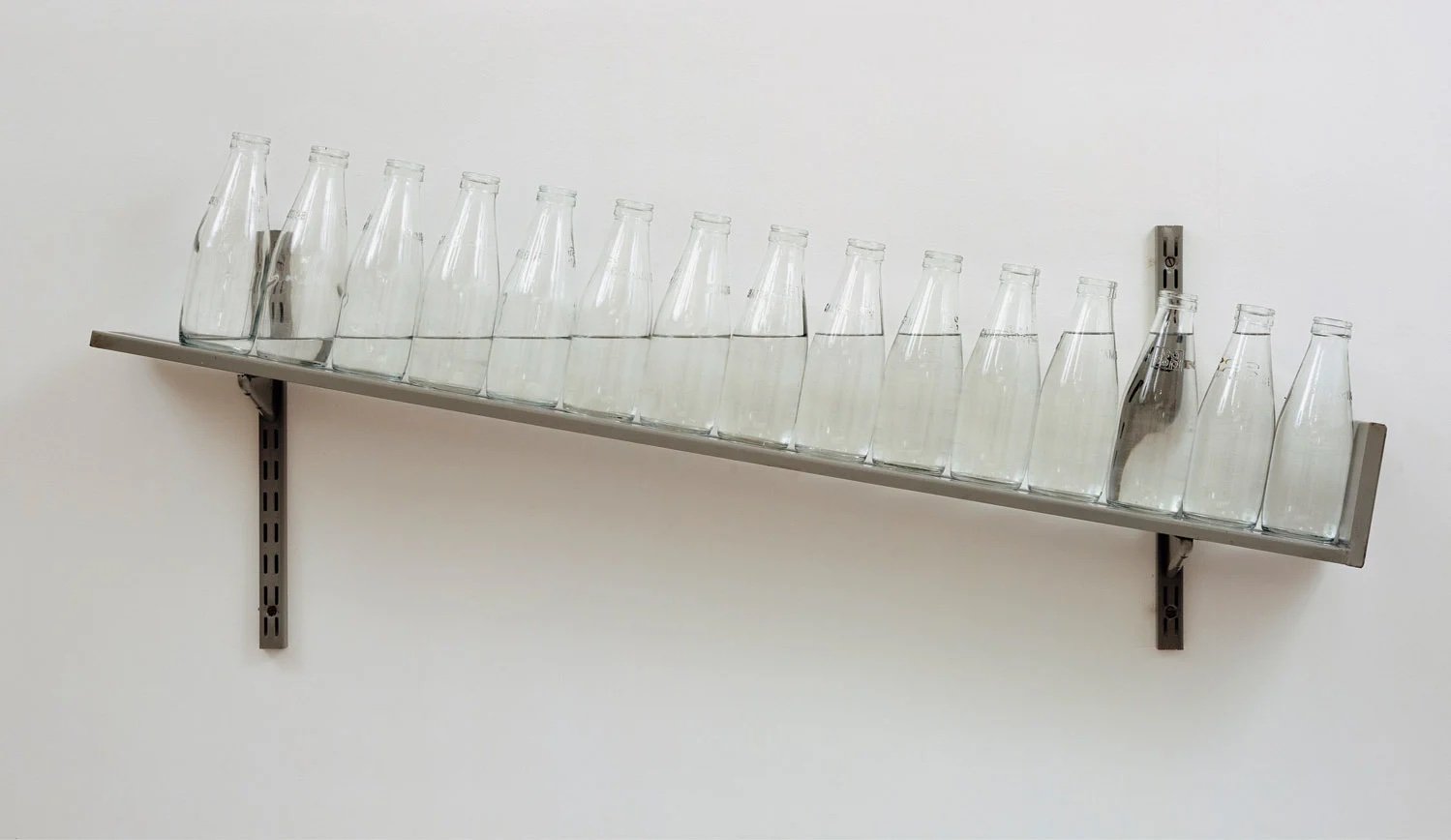

In the work, there’s a row of bottles, each with a measured level of water. I saw the water in each bottle as the “idea” itself, a quiet evolution held in balance on the shelf. At first glance, the water level in each bottle appears to form a perfect, unbroken line — serene and controlled. The water line seems continuous, each flowing into the next bottle. But as the gaze settles deeper, a tension arises. The bottles are set on a sharply sloping surface, tipped to the side, with a solitary stopper holding everything in place at one end. The tilt is precarious, the kind that begs you to imagine removing the stopper. I can’t help but picture it: the moment of release, each bottle tumbling down one by one, the fragile perfection shattered in an instant - an idea lost into oblivion.

This delicate structure— one that exists only because of a hidden, directional force — feels, to me, like the scaffolding supporting any idea. From the outside, a peaceful line of water, complete and self-contained. But below the surface, unseen forces shape it, hold it together, even push it in a certain direction. Here, the slope beneath the bottles presses the water levels into an orderly line. For the line to exist, each bottle must vary in its water level; it’s as if the water (idea) itself, aware of the slope, adjusts organically, adapting and deepening across each bottle from left to right. It brings a strange vitality to the piece, as if the water itself understands the delicate, pregnant tension of its setting.

In viewing this work, I can’t help but wonder: when we consume ideas, are we drawn to the harmony of the line itself, or to the hidden fluctuations that form it? This duality between the superficial calm and the underlying tension echoes the lifecycle of ideas. Just as each bottle’s water level is unique, my own ideas follow a logic I can sense but can’t quite map.

A mystery lingers, and it gnaws at me even as I step back from the work: where did the water come from in the first place? There’s room for another bottle at the far left, an empty space that suggests something missing, perhaps a bottle with no water. If the water stands for an idea, why not show the empty bottle to represent the origin? What lies just beyond, unformed, unspoken?